Behind the scenes with Britain's vehicle diagnostics experts

"Diagnosing a fault is like spotting food going off in a fridge" - Frank MasseyDiagnosis can be murder when modern cars break. We know just who to call

“We’re like mushrooms: fed s*** and kept in the dark.”

I’ve heard it before but it still makes me laugh. On this occasion, the person responsible for saying it is David Massey who, unless you’re into vehicle diagnostics, you’re unlikely to have heard of. David’s describing how independent garages are, he claims, denied essential technical information by car makers.

“There are the EOBD-II error codes that most drivers are familiar with and which correspond to a vehicle fault. They’re universal and can be interpreted by all garages. But then, running in parallel, are manufacturer-specific diagnostic platforms that require special software, and which generate their own codes,” he says.

“Manufacturers will argue it’s progress but it freezes out the small independent garage lacking the resources to invest in the required software, assuming they’d be granted access.”

Not that any diagnostic platform, be it EOBD-II or those unique to car makers, gives technicians the power to cure every problem. According to David, the error codes they rely on to identify a fault can themselves be misleading: “What’s your average tech going to do then, except hope he’s done something that causes the problem to go away long enough for the customer to pay up and take their car? Days later, the warning light’s back on and the car is in limp home mode – which is when people call us.”

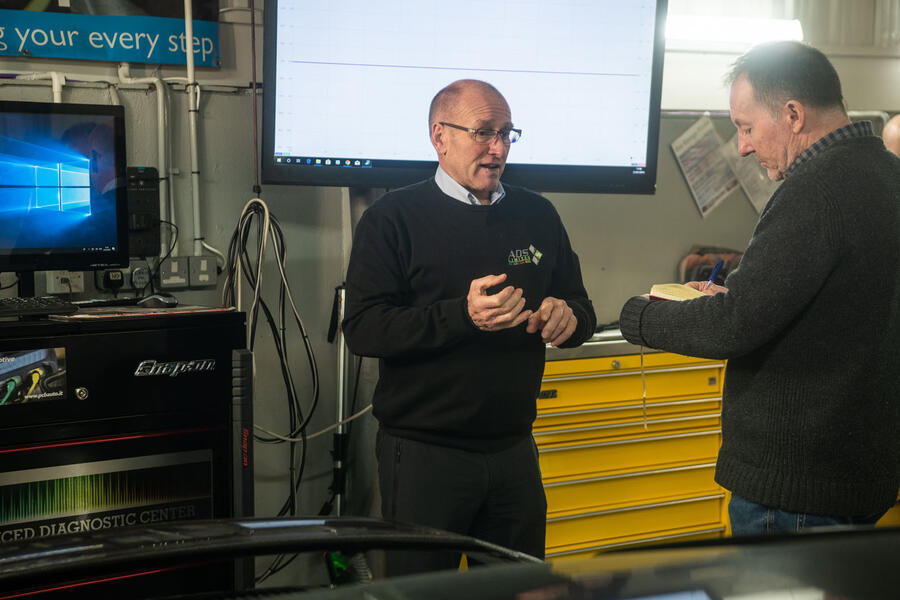

Error codes, diagnostics… it’s gobbledygook to me but, fortunately, I’m in the presence of experts: David, of course, but also Frank, his dad, known in the trade as the ‘guru’.

Frank is just back from Australia where he presented a series of tutorials in diagnostics to hordes of keen techs. Last year, he was in Italy (Modena, of all places), France and Ireland doing the same. He’s lectured to the military on Ascension Island and even to MI5, although his lips are sealed on that one.

I first heard his name on a recent visit to Ceramex, a Slough-based company that cleans diesel particulate filters. In a tone that suggested I should know the name, my host boasted that the facility had been visited by Frank Massey who had declared it fit for purpose. Having since watched Frank’s video tutorial on DPF diagnostics, I realise he was qualified to judge.

From Preston, where, with David, he own ADS, a specialist in Volkswagen Group cars, 65-year-old Frank heads up a diagnostics training school called Auto Inform. Topics include battery testing, misfires and emissions. Fascinating stuff but, if you’d rather stay by the fire, there are always his videos on YouTube; topics such as top 10 tests with PicoScope (a brand of oscilloscope) and the mysteries of diagnostic workflow…

Frank’s interest in diagnostics dates back to his time running Motor Masters, a vehicle tuning business he started in 1985.

“It was about the time new systems such as electronic fuel injection were coming into cars,” he recalls. “The trade hadn’t a clue how to work on them. I saw an opportunity, so got an oscilloscope and taught myself how to diagnose electrical problems.”

Frank quickly became an authority and began hosting training seminars, teaching technicians how to investigate and measure signal strength to determine the origin of a fault, rather than relying on half-measures like fault tracing charts.

Vehicle electronics moved up a gear with new emissions regulations in 2000 and the explosion in features such as air conditioning, electric windows, central locking and adaptive suspension.

“For garages and technicians it was like chasing a runaway train,” says Frank. “Simply to keep up required a huge investment in tools and training.”

Throughout, his faithful oscilloscope was by his side.

“A scan tool, or code reader, shows you the symptoms of a problem but an oscilloscope shows you its cause,” he says. “The former gives a tech only half the story; the oscilloscope reveals the profile of the signal and its flow. It’s the road map to a fault.”

Frank spots my eyes beginning to glaze, so gets straight to the point: “Imagine a tiny box. If all’s well within it – in other words, if a signal’s profile doesn’t stray outside it – no error code is triggered. But what if the signal’s extremes are teetering on its edge? It may be just enough to cause a problem but not to generate an error code.”

Frank explains how the ECU is constantly struggling to keep signals within these millions of tiny boxes, in the process generating ‘correction values’. Identify and understand these, he says, and you’ll find out what’s really going wrong: “Accurately diagnosing a fault is like spotting food going off in a fridge. How do you know? You use your nose, you check the sell-by dates… And to prevent it happening again, you control the environment.

“It’s the same with a fault, only we study the electrical signals flowing in and around the suspect component. Often, we find the root of the problem is not the component but the environment – temperature, oxygen levels, carbon deposits – that it’s operating in.”

He quotes the example of a customer at the end of his tether over a long-running problem with his four-year-old Audi A6 2.0 TDI. Frank established that the main dealer who’d been trying to fix the car had been misled by an error code and, running out of options, told the customer it needed a new selective catalytic reduction (SCR) system.

“In fact,” says Frank, “by examining signal strengths and flows, and the wider environment the SCR was operating in, we discovered it was the exhaust gas recirculation cooler that was at fault. Basically, it had an air block.”

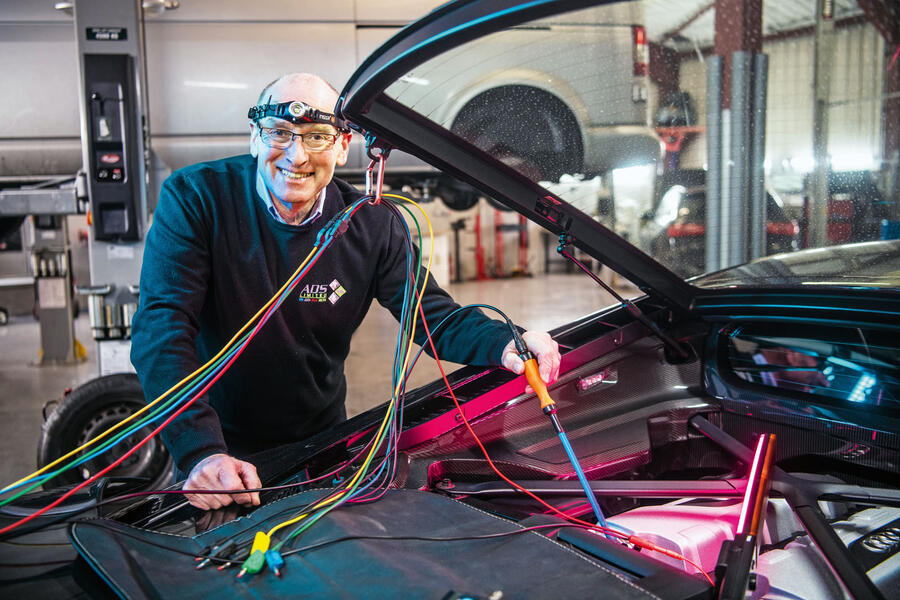

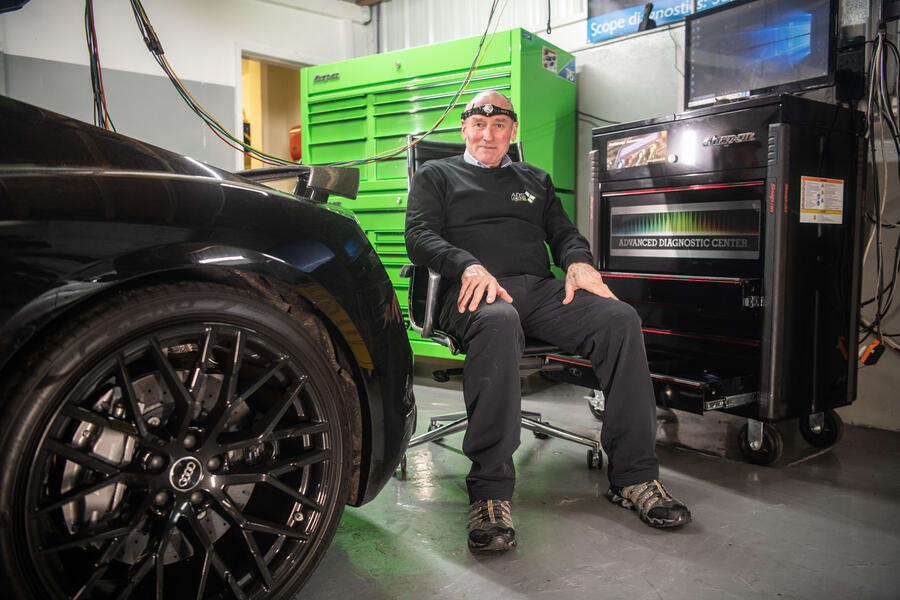

Interview over, Frank begins work on his next patient, an Audi R8. With his instruments laid out like a surgeon, an oscilloscope in his hand and a small LED light strapped to his head, he sets to from his favourite chair, illuminated by the glow of a large monitor displaying the car’s electrical pulses.

“He looks like a Cornish tin miner on Mastermind!” quips David.

Even gurus need a thick skin.

Speaking in code

Code readers or scanners aren’t just the preserve of professional workshops – you can buy one from as little as £10. Just plug it into your car’s OBD port (the car’s handbook should tell you where it is) and read off the error code on the display screen. Then consult the code book to find a description of the problem. Users swear by them, claiming they’ve saved fortunes in garage bills.

Vehicle diagnostics expert Frank Massey isn’t convinced.

He says: “The cheapest readers often have a very limited range of codes and their descriptions of the problem can be extremely vague. Remember: a code reflects the symptom but not its cause.”

Massey says vehicle- or manufacturer-specific code readers are a better investment. Where a generic reader might say ‘pressure sensor range error’, a dedicated reader would provide much more detail.

“If you have a VW Group car, buy a professional scanner such as the dedicated Ross-Tech VCDS,” he says. “It’s much more helpful and only costs £300 – a small price to pay if you’re a confident, amateur mechanic.”

Read more

Getting cleaned out: diesel particulate filters 10 years on

Comments

Post a Comment