Christmas road test: RNLI Shannon Lifeboat review

Each Shannon Class costs £2.2 million to build, and it's easy to see whyThe RNLI’s latest – and perhaps greatest – asset for saving lives at sea

If you’re in trouble on the water, the coastguard can, and very often does, request the assistance of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, the charity that has been saving lives at sea since 1824. And it is rather good at it: the RNLI rescues almost 8500 people every year.

If a lifeboat gets scrambled, there’s an ever-increasing chance it’ll be one of these: a Shannon class boat, the RNLI’s latest and greatest lifesaving tool. Crewed by six and capable of boarding up to 59 survivors, the Shannon is classed as an All-Weather Lifeboat, a term that, generally, means it can operate offshore and is so robust that it can safely go out whatever the sea conditions.

The Shannon owes its existence to the RNLI’s aim of reaching at least 90% of casualties who are within 10 nautical miles of the coast within 30 minutes of launching a boat in any weather. As a result, it wants its whole offshore fleet to be capable of at least 25 knots, so at least 80 of the RNLI’s 238 stations will eventually use a Shannon as it gradually replaces two slower classes of boat.

The first Shannon arrived on its station in 2014 and 26 are now in service. Designed entirely in-house by the RNLI and constructed in a new purpose-built factory at its Poole headquarters, Shannons cost £2.2 million apiece. New, innovative and proving to be exceptionally effective – in our tests, it proved to be rather quicker than its 25-knot design speed – the Shannon makes for the perfect Christmas road test.

Design and engineering

The RNLI designs its own boats because it has very specific requirements. Its boats need a unique blend of speed, manoeuvrability and stability. They must have enough durability and redundancy to operate for 50 years in appalling conditions, enough strength to tow other boats, the dexterity to operate in shallow waters and sufficient deck space to have people winched away by helicopter. They need to accommodate their crew and a large survivor space, yet still fit inside small existing lifeboat stations.

Oh, and to bring one of these boats ashore, the helmsman basically pins open the throttles and aims it at a beach, so it also needs to withstand that without sustaining damage.

Step forward a young RNLI naval architect called Peter Eyre, who first designed the Shannon’s hull shape as an experimental project. Narrow at the front and broad at the rear, it proved to be terrifically stable and rapidly became a production reality.

A production Shannon is 13.6m long overall (the hull length below the waterline measures 11.6m), and it’s 4.5m wide, with a draft – the depth below the waterline – of just 1m. The hull and superstructure, or wheelhouse, are made entirely from composites: mainly an epoxy resin sandwich, which is robust, light and easy to repair, with carbonfibre reinforcement in those areas requiring extra strength.

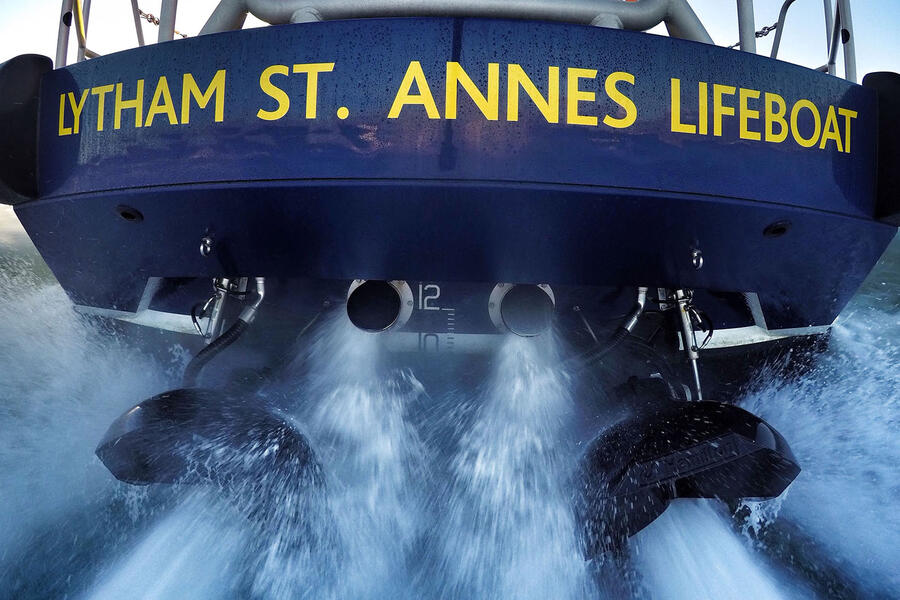

Uniquely for an offshore lifeboat, the Shannon uses a pair of waterjets rather than propellers. They give unparalleled manoeuvrability and help it operate in shallow waters, and between them have sufficient thrust to drive up to 1.5 tonnes of water per second from the back of the boat. The jets can be aimed left or right, but the clever bit is a pair of buckets that hinge hydraulically behind them. When the buckets are clear of the water, the boat drives forwards. Dropping them into the jets’ path deflects the water forwards and reverses the thrust in an instant.

As such, they can stop the boat in a heartbeat, hold it in position or crab it sideways in a half-open position, or, with one bucket up and one down, spin the boat on its axis. For the kinds of manoeuvre lifeboats frequently make, waterjets are proving invaluable, even if torque, for towing another vessel, isn’t quite as strong as with previous prop-driven boats.

Besides, nothing protrudes from the bottom of the hull, so the Shannon is easier to beach, where it’s recovered, and launched again, by a very cool Supacat tracked tractor and low-loader trailer set-up, which would be interesting enough for a Christmas road test. Some Shannons, mind, do stay afloat in harbour, while others use permanent slipways.

The HamiltonJet waterjets (basically tubes with a stainless steel impeller inside) are driven by shafts from two six-cylinder 12.7-litre Scania turbodiesel engines, mounted parallel to the hull centre line and making 641bhp each. In front of those are a pair of 1370-litre fuel tanks, so all of the major mechanicals are long and low in the hull, giving great stability and ensuring the Shannon self-rights if it capsizes.

There’s a huge amount of redundancy on board. The boat can run on either engine, which can take fuel from either fuel tank or through any fuel filter, and any of three banks of batteries and alternators, all of which are controlled by a SIMS – for Systems Information Management System – solid-state electronics system that runs the boat. And if all that goes wrong, the mechanicals can be operated the old-fashioned way.

All of that means a Shannon tips the scales at around 17.9 tonnes, about twice the weight of a powerboat of similar length but with a lot more than twice the capability.

Interior

Step through the watertight rear door and there’s a marked difference between the brightly coloured exterior and the predominantly black cabin. There’s actually quite a generous window area, made from 10mm-thick polycarbonate panes, but this is still an interior that absorbs light, for the very good reason that doing so reduces reflections and improves the view out.

The floor is non-slip coated and there’s a single aisle between two columns of big, luxurious seats, mounted on shock-absorbing coil-over dampers and with race harnesses. The two on the left are for the helmsman (front) and mechanic (behind), the three on the right are for a navigator (front), coxswain (middle, the chief of the boat) and a second navigator (rear, who also has a chart table). There’s a centre seat at the back for a sixth crew member, often a doctor, in front of which, in the aisle, there are flush brackets to locate one of the stretchers stored below. Dark curtains can be drawn to separate areas of the cabin – if a casualty is being treated, for instance, so a doctor needs light but the navigators need darkness.

The five window seats all get a SIMS display screen, individually dimmable and with a trackball and control buttons with plenty of inertia. (The novelty of touchscreens in a force 12 storm would probably wear off pretty quickly.) The SIMS displays control not just the boat’s mechanical systems and redundancies, but also the communications and navigation.

We set out from Poole into a choppy English Channel and then a much calmer Solent. The damped seats are exceptionally comfortable but brilliantly subtle. Only when you look across the aisle do you see how much they’re moving and how much of the crashing they’re damping. The wipers have an intermittent setting, there’s cabin heating and air conditioning via vents that demist the windows, and there’s a small hot water boiler and cupholders. But no loo, so go easy on the tea.

At the front of the wheelhouse, a hatch leads to the survivor space, which houses six harnessed seats in a light grey cabin. You can fit 20 survivors inside and the boat will still self-right, but a Shannon is rated stable even with 59 survivors on board.

Back inside, there’s a storage space in the nose and, behind the survivor space and below the wheelhouse, three more compartments: one each for fuel tanks, engines and waterjets.

The boat is four metres tall and the superstructure accounts for well over half of that, so head room is pretty tight in the mechanical spaces. Each compartment has a watertight door and any two of a Shannon’s six spaces can be completely flooded and it will remain afloat.

On deck, which we’re going to count as ‘interior’ for these purposes, there are steps to an upper steering position (USP), which has one SIMS screen and all of the driving controls replicated, except that the helm joystick is swapped for a wheel.

Performance

The Christmas road test is always at its best when we can attach our data-logging kit to the subject. And so in a sheltered bit of the Solent, we suckered the timing gear to a flat exterior surface, went back inside, asked the helmsman to give it everything and hoped the equipment wouldn’t fall off. Which it didn’t.

Mariners work in knots but mph suits us, so we adjusted for tides and winds that could make, say, 0-10mph actually 2-12mph on our GPS. Readouts in the cabin show both true speed and ground speed.

The Shannon is designed to reach 25 knots (28.8mph), but it’s much faster than that: at full chat, it’ll hit nearly 32 knots (36mph). It takes a while longer than a car to get there, due to the fact that water is 50 times more viscous than air and a Shannon weighs 18 tonnes, but from rest, it’ll be at full speed within 35sec and 420m, which is impressive.

But not as impressive as the way it stops. Dropping the buckets and reversing thrust slows a Shannon from its max speed to stationary in just 57m in a straight line, but even that’s not the fastest way to do it. Throwing one jet into reverse and cranking the steering to the side, a kind of maritime handbrake turn, will have a Shannon sideways in just 20.5m, barely more than its own length, from top speed. Keep turning on that trajectory and it’ll execute a U-turn with a diameter of 48m, with peaks of 2.8g. Hence the harnesses.

Ride and handling

Watching an expert at the controls of a Shannon at speed in choppy seas is quite a sight. The steering lever is barely left alone and it’s striking just how quickly, compared with conventional boats, a Shannon can be manoeuvred and aimed. At higher speeds, the buckets are adjusted as one to rapidly slow and accelerate the boat, whose hull cuts through the tops of waves rather than rebounding over them while the spats towards the front reduce spray.

Most of a Shannon’s work on operations is performed near full throttle, at around 2200rpm on the engines, so the jets are pushing out their 1.5 tonnes a second and loads of power is available. That makes the boat brilliantly responsive. Even when stationary, with a neutral bucket position at lower revs and fore and aft forces still being exerted, it’s more stable than a prop boat idling in neutral – like a hovering helicopter rather than a balloon on a string.

Another excellent thing about jets and buckets is that you’re only rapidly adjusting a few, cheap, robust parts, while the impeller, engine and gearbox operate in a steady-state, and therefore lower-stress, condition.

Buying and owning

At idle, around 600rpm, the Shannon’s engines will burn about four litres of fuel an hour between them, although that won’t get you anywhere very quickly. At typical cruising revs of around 2000rpm, the engines get through 170-190 litres of fuel per hour, but crews are usually in a hurry so they operate for long periods at 2200rpm-plus, which burns fuel at nearly 240 litres per hour and equates to approximately 1.5 miles to the gallon, depending on speed. The Shannon’s range, whatever, is at least 250 nautical miles at full speed in heavy seas.

The Shannon turnaround time can be brisk. The recovery trailer is also a turntable and can turn the boat around for a relaunch in just a few minutes. Once ashore or back at harbour, each fuel tank can be refilled at 200 litres per minute.

A Shannon will spend 25 years in service, and following a refit be good for another 25. Reliability is reportedly good, although constant running at full revs can make the turbos a bit hot and bothered, which is understandable.

You can’t really buy a Shannon, although if you donate enough, they’ll name one after you. If you go to the rnli.org website (and we heartily recommend you do), there are ways you can help out a fine organisation.

This is an institution that largely runs on volunteers, but there is a full-time mechanic at each station and a significant training and support operation. Keeping 500 boats and 238 stations going costs nearly half a million quid a day, all of which is raised by donations.

Such is the cost of rescuing almost 8500 people a year. On average, the RNLI gets 24 call-outs every single day, so there’s a pretty good chance a rescue is taking place while you’re reading this.

Verdict

When somebody volunteers to get out of bed at 3am in the middle of winter and within 10 minutes finds themselves at the foot of a 14m-plus wave in a boat not even 14m long while contemplating going out on deck to save lives for no motive other than their compassion and a desire to help people, it seems only right to give them the best possible equipment with which to do it.

And therein lies the motivation to give the Royal National Lifeboat Institution’s 4500 volunteers the best lifeboat money can buy, and where the best doesn’t yet exist, to go ahead and build it so that it does. The Shannon class lifeboat is evidently the most tremendous embodiment of that, a brilliantly versatile, durable, manoeuvrable and rapid platform for rescuing people and saving lives. It just so happens that it’s an incredibly cool piece of kit, too. We loved it.

Tester’s notes

The survival space is bright but can be auto-dimmed to a red light when the hatch is opened, to prevent glare in the main wheelhouse.

The rugged hull is coated with four different layers of paint – black on top, then yellow, red and grey – which wear when the boat is beached. Once the grey is showing through, it’s time to reprotect it.

Spec advice There’s only one option: the strop for the sea catch. Whether the boat lives inside or is a float boat (and stays moored) determines if it gets one.

Jobs for the facelift Lordy, we don’t know. An extra cupholder? More towing oomph? Nothing of any substance.

WE LIKE:

- All-weather capability

- Speed and manoeuvrability

- Can hold an extremely large number of people

- Beach launch potential

WE DON'T LIKE:

- Honestly, nothing of any consequence

MODEL TESTED: SHANNON CLASS

Price £2,200,000

Power 1282bhp

Torque 3850lb ft

0-30mph 28.8sec

Fuel economy 240 litres/hour

Max speed-0mph 20.5m

Read more

Christmas road test 2017: 1948 Peppercorn A1 ‘Tornado’ steam locomotive review

Christmas road test 2016: HMS Bulwark Royal Navy amphibious assault ship review

Comments

Post a Comment