Under the skin: how turbochargers have evolved

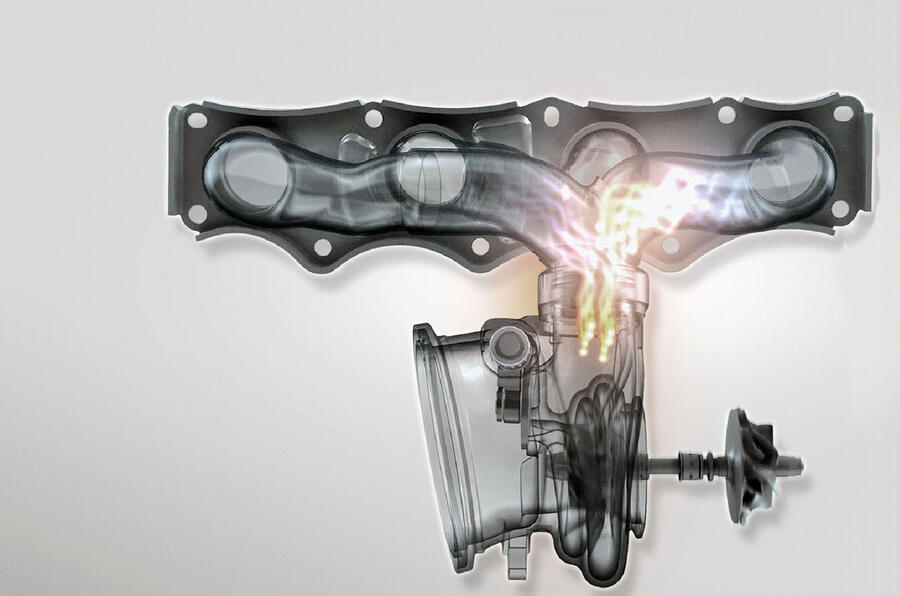

Energy from expanding exhaust gases on the ‘hot side’ drives a compressor on the ‘cold side’ to force air into the engine under pressureWhere did all the lag go? We look inside the modern turbo to see how it improves engine response and reduces emissions

Turbocharging has evolved over the past few decades from being a novel, if laggy, gadget for gaining cheap power to much more than that.

It has played a huge part in giving all fuel-burners a new lease of life, taking a lead role in reducing emissions. Turbochargers allow downsizing, the shrinking of petrol engines into smaller, lighter, more efficient engines producing fewer emissions, without compromising power and torque. They also feed diesels the massive amount of air they need for lean, air-rich combustion.

In the beginning, engines were naturally aspirated, relying on atmospheric pressure to draw in air. So getting atmo engines to produce more power and torque ultimately means increasing the capacity. Hence that famous American saying: ‘There ain’t no substitute for cubic inches.’

Boosting air into the engine under pressure allows more fuel to be burnt, thus releasing more energy. Glorified air pumps, turbos straddle exhaust and air intake systems. When the driver hits the throttle, superheated exhaust gas bursts from the engine into the turbo’s ‘hot side’ with explosive force. The ferocious energy unleashed by the expanding gases is so violent, it can accelerate the turbine inside to as much as 300,000rpm in milliseconds.

In the ‘cold side’ compressor housing, an impeller sucks in cold air and crams it into the engine via an intercooler. It sounds like something for nothing, but it isn’t. There’s a price to pay in the engine overcoming the exhaust back pressure caused by the turbocharger, but the extra power the engine can generate is much higher.

To shed unwanted boost when the driver lifts the throttle, there are typically two valves – a wastegate and a recirculation or ‘dump’ valve. The wastegate lets exhaust dodge past the turbine and, on the intake side, the dump valve simultaneously opens to vent pressure from the intake system. When the driver hits the throttle again, both valves close and the boost is back.

Today, turbos are highly refined. Lag is minimal thanks to lower inertia of smaller rotating parts, high-tech bearings and clever turbine and impeller aerodynamics. Different types have emerged, too. In twin-scroll turbos, the exhaust gas leaving the engine is split into two streams and fed into two separate ‘scrolls’ inside the snail-shell-like turbine housing. Response is improved by using exhaust pulses to best effect.

Variable turbine geometry (VTG) turbochargers are even more effective at cutting lag at low engine revs when the energy in the exhaust is at its most reduced. But they are costlier and, with a few exceptions, have so far been mainly confined to diesels, because fiddly internals cope better with the diesel’s cooler exhaust. Even costlier ways of improving response are sequential turbo systems with two turbos, large for high-power output and small for slow-speed response.

Save with a twin scroll

BMW launched twin-scroll turbocharging on its then-new 2.0-litre turbo back in 2011. It featured a fabricated (from steel sheet) exhaust manifold to reduce costs. Even better, the twin-scroll turbo also delivered most of the response benefits of a variable turbine geometry turbo at a lower price.

Read more

How to look after your turbocharged car

Comments

Post a Comment