Christmas road test: 1948 Peppercorn A1 ‘Tornado’ steam locomotive review

Forward visibility isn’t great and the seats are pretty rudimentary but there’s lots of headroom and the raised driving position puts even the loftiest SUVs to shameThe newly built A1 'Tornado' has returned 100mph steam power to Britain’s railway network - and had a starring role in Paddington 2. We took the controls and subjected it to our full road test

Arthur Peppercorn was, by all accounts, a modest but exceptionally talented man.

When he became chief mechanical engineer of the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER) in 1946, he designed and oversaw the engineering of a number of steam locomotives. Among the best was the Peppercorn Class A1, designed as passenger express trains for the arduous London to Aberdeen east coast mainline route, on which they would haul as many as 15 carriages, each weighing up to 550 tonnes.

Read all of Autocar's in-depth reviews (of cars, obviously...)

In 1948 and 1949, some 49 Class A1s were built, but within 17 years, as steam power gave way to diesel and electric, all had been withdrawn. None was saved. And that was that.

Until, that is, 2008, when a new Peppercorn A1 locomotive was made, the 50th to be built. It was called ‘Tornado’, and this is it.

So why road – or should that be rail? – test it now, nine years later? There are two reasons. One is that it gives your correspondent a valid excuse to watch Paddington 2, a film in which Tornado stars, on expenses. The other, more significant reason is because in April this year Tornado became the first steam locomotive in 50 years to reach 100mph on the UK rail network.

Retro: is a Channel Tunnel feasible? (from 1935)

And that’s important because, while most UK heritage trains pootle up and down their own specific lines at perhaps 25mph, a few, like Tornado, use the regular mainline railways.

Tornado had previously proven that it can run at 75mph – in fact, in rigorous, frequent safety checks, it proves its integrity time after time – but most commuter trains will hit 100mph these days and inter-city trains rather a lot more again.

So Tornado’s operators went to seek approval to run at 90mph, so it can fit more easily onto a busy national rail network during the excursions it runs for paying passengers. It’s a speed it had to exceed by 10% to be accredited. And, well, if they were going to have to prove themselves at 99mph…

So that’s why Tornado is here now. We’re going to tell you how it works and, crucially, how you’d drive it if you found yourself on the footplate. All aboard.

Design and engineering - 5 Stars

Tornado was made to, as close as possible, the same design and engineering standards as the original Class A1 steam engine, barring a few regulatory differences, which we’ll come to in a moment.

It is a vast traction engine. There are two main elements: the engine, which houses all the mechanicals, and the tender, which contains the fuel (in the form of coal) and water. Tornado wants rather a lot of both of those. Together, the engine and tender measure 22 metres end to end and weigh 169 tonnes when full.

2016 Christmas road test: HMS Bulwark

The workings of a steam engine are intensely complicated (hence the attraction of diesel and electric trains, we suppose), but here goes. There is a boiler, German made, within the green cylindrical section above the wheels. It consists of more than 200 tubes and elements of varying sizes, into which water is pumped, whereupon it’s turned into steam by the heat from a 4.65-square-metre – 50sq ft in old money – coal fire, lit beneath the rear of the boiler and stoked by hand. All in there are 293sq m of heat-exchanging surfaces.

The boiler needs to be pressurised to as close to 250psi as possible to make good steam. Any more and it’ll blow off through a release valve. A regulator, which is what you and I would know as a throttle, allows steam out of the boiler and into a smaller steam chest, from where it passes uninhibited into Tornado’s pistons. There it expands and pushes a rod that’s offset on the wheel, which turns a reciprocating mass into a rotating one. Hey presto, wheels turning. Whatever pressure you allow in the steam chest is the pressure that will drive the wheels, so there’s a delay to your regulator/throttle inputs – “a bit like turbo lag,” says the Tornado’s driver.

There are three of those pistons. The outer pair each drive a centre wheel, while an unseen middle piston drives the front axle. Each axle is linked together, though, so Tornado is six-wheel drive.

What’s remarkable is that these huge, 2.03m-diameter drive wheels each have a footprint of just 2.5sq cm or so of metal touching the tracks. So despite Tornado’s size and weight, an enormous amount of tractive force has to go through a very small surface area. It’s why you so often hear trains chuff quickly when they lose traction at low speeds: too much pressure goes into the steam chest and it takes a few moments to dissipate into wasted revs. Some support staff say they can tell who’s at the controls from the way the engine is being driven.

The amount of steam used in each piston stroke depends on how fast you’re going. At low speeds, where plenty of accelerative oomph is required, lots of steam is let in per stroke. As speeds rise, that’s eased back, via a control in the cabin (it has a neutral point in the middle; wind it far enough and you’ll find reverse), so that expansion rates are anything between 25% at low speed and 75% once you’re really shifting. As the piston moves an exhaust valve is presented. Through it excess steam passes and heads into the smokebox – within the black painted area at the front. Even here it’s still useful: it draws heat through the firebox as it mixes with its smoke and passes out through the chimney.

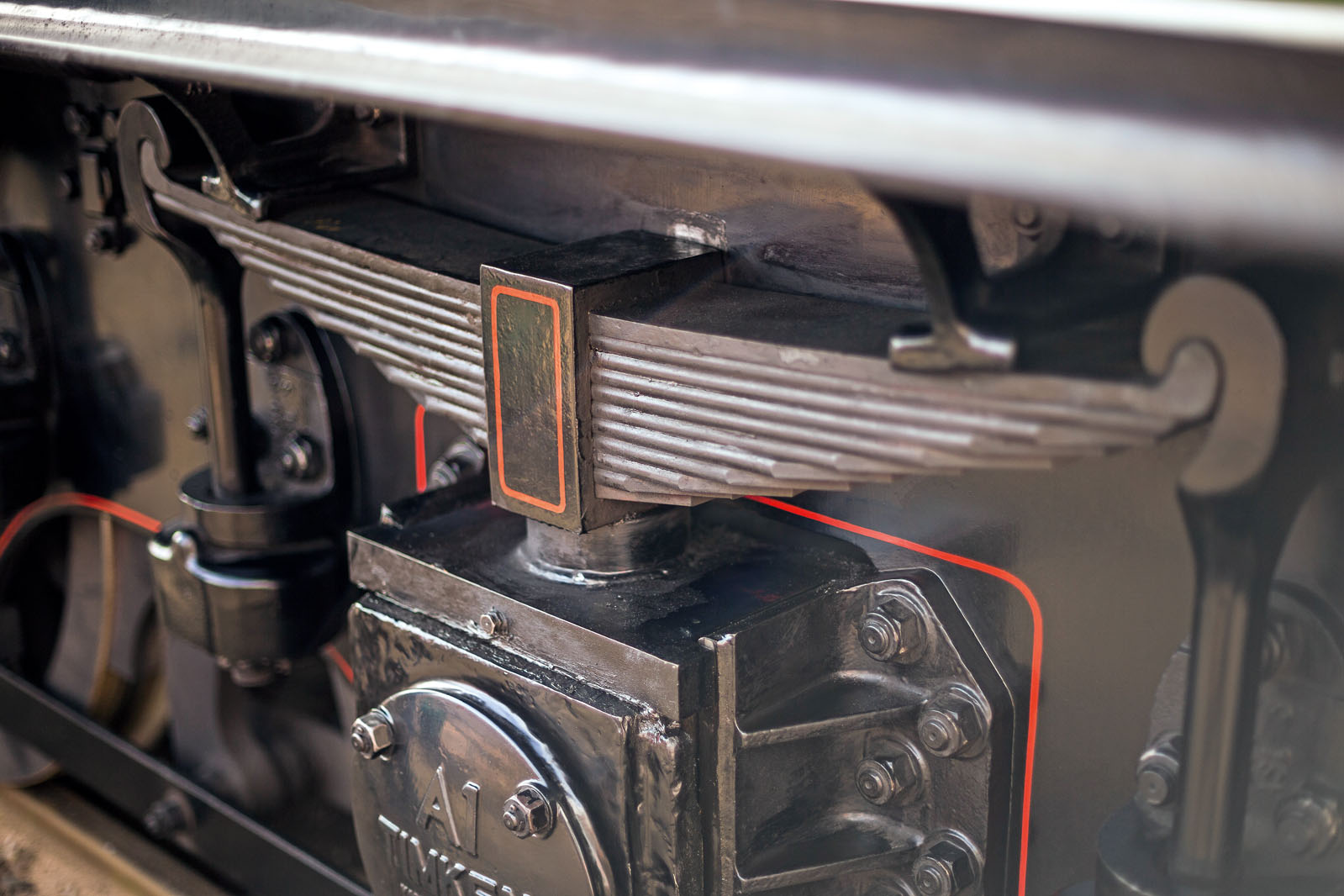

Tornado is a Class A1 engine to the extent that “outwardly, it’s the next step in the class”, but there are some changes over the 1940s engines. Tornado runs with roller bearings, which last longer and are lower in friction than ball bearings, while today it has to run a regulatory radio system and a modern air brake rather than a steam brake, and it has to be a touch lower than the original engines because of overhead power cables.

There’s also no need for the tender to have a water scoop beneath it, as it would once have had. Instead, its 7.62-tonne coal capacity and 28,011-litre water capacity have to be filled trackside by special arrangement. Which is a little less practical but nonetheless inevitable.

Interior - 5 Stars

There are places on a steam train that are quite palatable: in the back, for example, sitting in a dining car, being served fine foods. But your area of interest and mine happens much nearer to the front, on what they call the footplate, which is the bit between the engine and the tender.

Here it’s hot, filthy and noisy, and you can’t see out very well. You’re also faced with what looks like – and in fact is – a baffling array of controls. Some are more frequently used than others but they’re all fairly important. So let’s go through them and, by the end, we should know how to drive a steam locomotive.

Just above the floor is the firebox. That’s the hot bit, obviously. The fireman in charge of it sits on the right, when he isn’t standing and shoveling coal, that is. The wide pipes with big valves on that run up each side of the firebox allow water from the tender into the boiler, and there are two glass gauges that show how full that is. There are two because it needs a degree of redundancy: should the boiler run dry when it’s hot, it will probably explode, which is an unhappy fate to befall a steam locomotive and those on or near it.

Another potential peril is the water in the steam chest, because while steam compresses, water does not, so there is a release valve to blow any out before setting off. It’s why you’ll see engines emitting steam from the front before they go anywhere.

There are, in effect, seven steps to driving a steam train, once you’ve done the necessary preparation. It takes a couple of hours to build up boiler pressure before a run, and to do it you’ll want a good, glowing fire throughout. Black patches, or holes in the fire, are unwanted cool spots. First, then, get the boiler up to pressure. Once it is, wind the drive handle into the gear you want, either forward or reverse.

2015 Christmas road test: East Anglian Air Ambulance

Second, ensure the locomotive brake is on. This is an air brake today, driven by a steam-powered air pump beneath the engine. Third, wind the handbrake off – you’ll find it behind the fireman. fourth, take authority from a signalman. Fifth, check it’s clear, on both sides. Sixth, sound the whistle. Seventh, release the air brake and pull the big red regulator lever. And you’re away, driving a train.

Performance - 5 stars

Acceleration from rest is pretty glacial, which is no surprise if you’re pulling 458 tonnes behind a 161-tonne engine, as we were on our return trip from Derby to Newcastle, even with 166.38kN of tractive effort (not brake horsepower) to hand.

Traction is unsurprisingly limited, and that whole ‘leaves on the line’ thing isn’t just an act. The sap they give off can, apparently, be particularly slippery. Tornado has sand dispensers to help it find traction in difficult conditions.

Once it builds its momentum, and develops an endearing, regular chuff that’s all but inaudible once you’re two carriages back, Tornado holds its speed impressively.

At speed, the driver spends an inordinate amount of time acknowledging an air horn that sounds every time you pass a signal, while the fireman’s job is to maintain the correct steam pressure and water level. He shovels coal from the tender into the firebox, with deft flicks of the wrist to keep the fire even. At full chat, the fireman might shovel 30 to 40 loads into the firebox in one go then have two minutes off, to monitor the firebox or talk to the driver about an upcoming stretch of track.

It’s easy to think of steam engines as rather inefficient old things. But it’s rather extraordinary to think that one person can shovel sufficient energy, by hand, to keep a 600-tonne train at 100mph.

Ride and handling - 5 stars

Can we live without a ‘corners like it’s rails’ analogy? I think we probably can. What’s notable about the driving experience of Tornado, though, is the amount of feel that goes into it. You don’t get feedback from the controls – the regulator is just a large red handle and the steam chest it powers has lag to it – but you feel if the engine is on song or struggling, say drivers, through your legs and backside.

2014 Christmas road test: HondaJet

Only drivers who know a particular stretch of track are allowed to pilot Tornado on that route. By day, they’re regular train drivers, but they have built working relationships with their firemen and with the engine, and the better they understand both, the more efficient they’ll be at the job of driving.

Adding coal to the fire, for example, at first makes the fire colder, not hotter, thus reducing boiler pressure. So if there’s an incline ahead, the fire needs fueling in advance to build enough heat to maintain pressure on the climb. If a downward stretch is approaching, the engine might be backed off, and when there’s a finite amount of fuel and water on board, it’s evident if you’re more efficient. There’s a real craft to it, because the more efficient a driver and fireman are, the less fuel and water they use getting to where they’re going.

Buying and owning - 5 stars

It took £3 million to build Tornado, so if you’re thinking of buying a steam train, at least now you know what you’re up against financially.

But when it comes to owning, so long as there are paying customers, and bears in moving pictures, Tornado will have its way paid.

Fuel and water are the bigger headaches today. On our journey the water tender was filled three times – on the way, in Newcastle and on the way back – and coal filled at Newcastle. It’s reckoned Tornado got through six tonnes of coal. By our reckoning that’s about 60 miles per tonne, although its maker quotes an average nearer to 39 miles per tonne, which in turn equates to 23,205g/km of CO2, so you probably don’t want to run one as your company vehicle.

The bigger problem is the running of a non-essential train on the UK’s general rail network. There were two issues on our journey. One was when a commuter train driver finished a shift at Newcastle and abandoned the train at a platform with no replacement driver, creating all sorts of delays. The other was a broken signal, which meant diverting trains to another line and hastily rearranging a water tanker. Tornado can, and does, run like clockwork, but it’s still at the mercy of the network.

2013 Christmas road test: McLaren Specialised S-Works + McLaren Venge bike

Technical layout

Tornado is a 4-6-2 wheel arrangement, 1435mm gauge steam locomotive. Four-wheel bogie at the front, with six driven wheels and two trailing wheels. Three pistons, six-wheel drive, with a minimum crew of two on the footplate, which is situated between the engine and the tender.

Verdict

A perfect mix of engineering, transport and pleasure.

As you chuff past green fields and country lanes on a speeding steam train, two things quickly become apparent: first, steam locomotives alarm wildlife, and second, they absolutely fascinate people, who are intrinsically drawn to this puffing, heaving, mass of iron and machinery. Partly, we suppose, it’s nostalgia.

But there’s more joy to Tornado than that. Driving it is far more than just a mundane but responsible job. No, understanding the engine is a real craft, and getting the best out of it, and driving it in the most efficient way possible, is a tremendous skill.

Small children didn’t grow up wanting to be engine drivers because it was noisy, smelly and tiring; they wanted to do it for the same reason they want to be racing drivers or pilots, or chefs, or horse riders, or farmers: to experience the great personal joy that comes from being good at something that takes time, dedication and understanding to master, especially if it’s exciting at the same time. With Tornado, that appeal burns as brightly as ever – and it’s chuffing brilliant.

Testers notes

Most of the controls are reassuringly weighty, and a few are warm whether you want them to be or not. Standing on the footplate is a pretty heady experience.

Spec advice Not much choice here. If I were ordering one I might pick an alternative colour, just to be different. Otherwise you get your A1 locomotive in authentic specification, only with added headlights and updated safety kit.

Jobs for the facelift Well, a facelift isn’t really the point. But could the door to the firebox not open a bit wider? It’s easy to clang shovel against metal.

WE LIKE:

- 100mph performance

- Intoxicating sights, sounds and smells

- Opportunity for ‘chuffing’ puns

WE DON’T LIKE:

- Expensive to build and run

- Requires large support crew

- Limitations of the UK’s rail network

CLASS A1 STEAM LOCOMOTIVE:

MODEL TESTED: 60163 ‘TORNADO’

Price £3,000,000

Power 2400bhp (approx)

Tractive effort 166.38kN

Fuel economy 49 miles per tonne of coal

CO2 emissions 23,205g/km (approx)

Top speed 100mph

Read more

Read all of Autocar's in-depth reviews

Retro: is a Channel Tunnel feasible? (from 1935)

2016 Christmas road test: HMS Bulwark

2015 Christmas road test: East Anglian Air Ambulance

2014 Christmas road test: HondaJet

2013 Christmas road test: McLaren Specialised S-Works + McLaren Venge bike

Comments

Post a Comment