Past masters meet their modern-day matches: trailblazers on trial

The Quattro is still dazzlingly fast but more cumbersomePerformance icons should be remembered for leaving their peers for dust, not measured against those younger and leaner. Still, it makes an interesting then-and-now comparison, as Andrew Frankel discovers

Performance is an entirely relative thing: there are times when 40mph can be lethally fast - approaching a school at chucking out time, for instance – and others when 600mph seems desperately slow, such as eight hours into a 12-hour flight.

So perhaps we should not be too surprised that road car performance that was once seen as groundbreaking now seems really rather normal. But how long does this process take? How long is required for the once completely extraordinary to seem really rather ordinary? To find out, we've gathered together three limited-edition old-stagers whose performance in their category was once groundbreaking to see how they’ll do against their brand new, mass-market descendants.

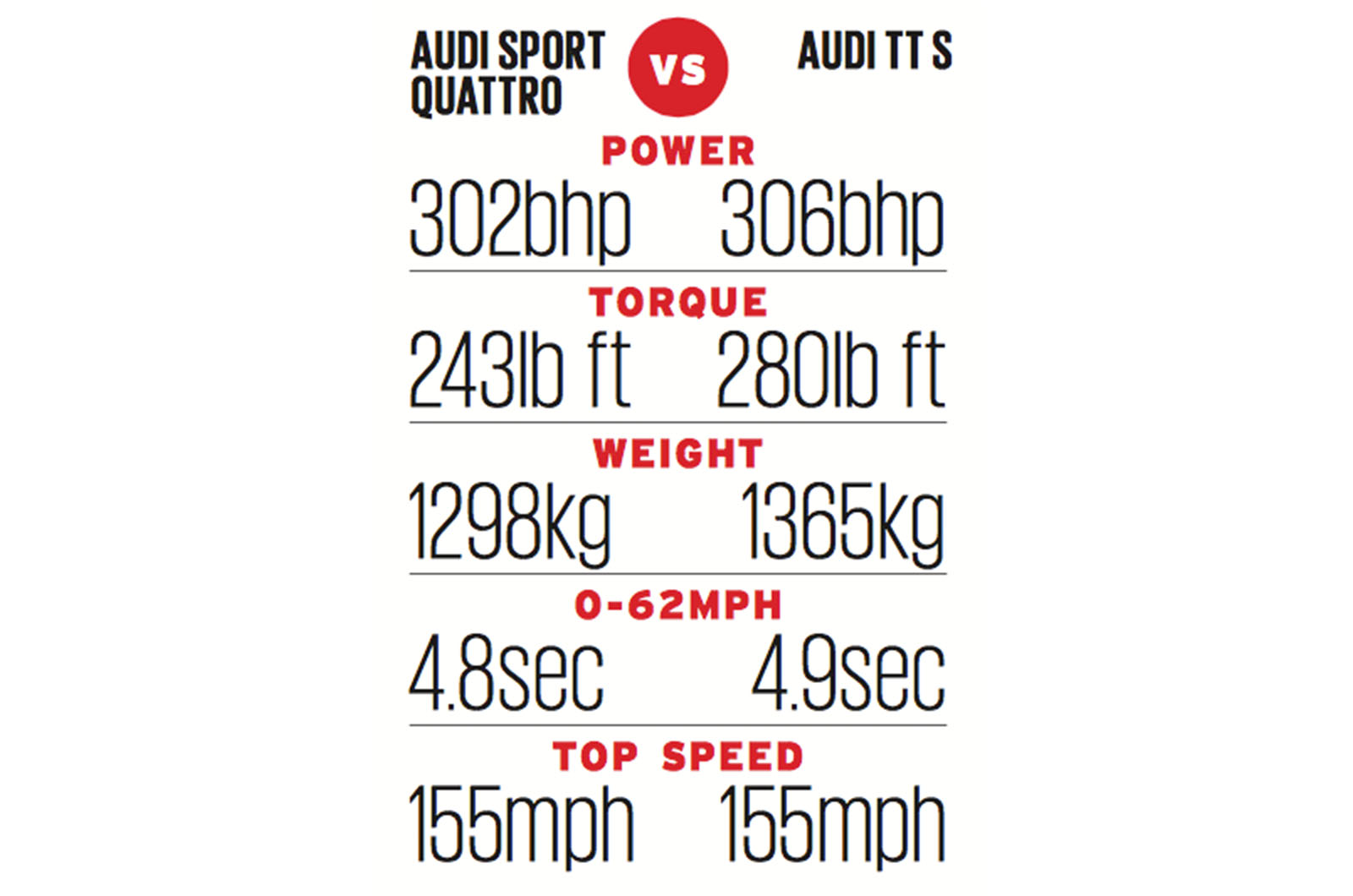

Audi Sport Quattro (1983) vs Audi TT S

It's possible that the point we’re trying to make here will never be more vividly demonstrated than by the two Audis we’re testing.

In one corner stands a beast of near-mythical ugliness and reputation. The 1983 Audi Sport Quattro is rallying royalty, a pure homologation special of which just 200 were required to make its competition derivative, the S1 Quattro, eligible for the World Rally Championship. Back then, the sight of even a standard Audi Quattro would make people walk into street furniture. So imagine such a car with a frankly insane 320mm cut from its wheelbase and clothed in carbonfibre-reinforced Kevlar bodywork toting bulging wheelarches.

But under that uniquely pugnacious skin, it was madder still: Audi designed a brand new twin cam, 20-valve head for its five-cylinder engine and then, because the rules applied a multiplication factor of 1.4 for turbo engines, dropped its capacity by 11cc to 2133cc so it could squeeze under the maximum 3 litres allowable. That this provided more than 300bhp from such a tiny engine seemed the stuff of fairy tales: a Porsche 911 Turbo of the era produced less power from 3.3 litres, while even the super-specialised world’s fastest car, the Ferrari 288 GTO, could not match its bonkers 142bhp-per-litre specific output.

But a 2017 Audi TT can. In fact, you don’t even need the red-hot RS version to do it. A nicely warmed TT S will get there with space to spare, offering just a little more power from an even smaller engine. But it’s half a tonne heavier, right? Wrong. Despite all the airbags, bum warmers, sat-nav systems, sound deadening and myriad other niceties forced upon such cars by the marketing requirements of the modern world, with one person aboard it weighs the same as the Kevlar Quattro does with two, a difference more than offset by its fat band of additional torque.

For hacks who have been around a while, the Sport Quattro is a magical step back in time. Although I’ve not sat in one for years, the interior – with its chunky switchgear, brilliantly clear dials and thick Recaro seats – seems familiar. Even by Sport Quattro standards, this car is special, because it's utterly original and has never been mechanically restored.

At first, I think it’s broken. The engine still makes that delicious five-pot burble, but as I accelerate down Bruntingthorpe’s runway, there seems to be quite a lot of smoke out of the back and next to nothing in the way of power from the engine in the front. I’m on the point of giving up when the white cloud behind the car disappears because it’s not smoke at all, just steam from condensation in the exhaust. But there’s still no power. 2000rpm comes and goes, then 3000rpm, then there’s a little twitch from the boost gauge in front of me and then, at about 3500rpm, the needle flicks full over and the Quattro is off, prow sniffing the air, engine wailing its inimitable song. Even now it feels fast: in 1983, it must have seemed like witchcraft.

But if I’m honest, it feels cumbersome too. The whole point of biting such a chunk out of the wheelbase was to increase its agility so it might compete with purpose-built mid-engined rivals such as the Lancia 037, but the Quattro still feels nose-heavy, which, combined with the enormous turbo lag and a slow gearbox, means the car has to be driven very precisely and in a certain way. Do so and it’s a joy, but I’d be lying if I said it didn’t feel its age, even more so than the BMW M3.

By comparison and more than anything else, the TT S just feels easy. Around a track, it would obliterate the Sport Quattro, not least because all that time and brainpower the driver of the old car spent making sure it was being driven just how it wanted can be devoted to the simple business of going fast. The TT not only has more torque, but it develops it in fewer than half the revs, and the DSG automatic gearbox in the test car made dispensing it easier still.

The surprise, at least to me, was how entertaining the TT S was. Audi has mistaken fast for fun more than any car marque, and any car as quick and capable as the TT S runs the risk of excluding the driver from the process. But not this time: it felt not just rapid, but nimble and involving too. To me, it was the surprise package of the entire group.

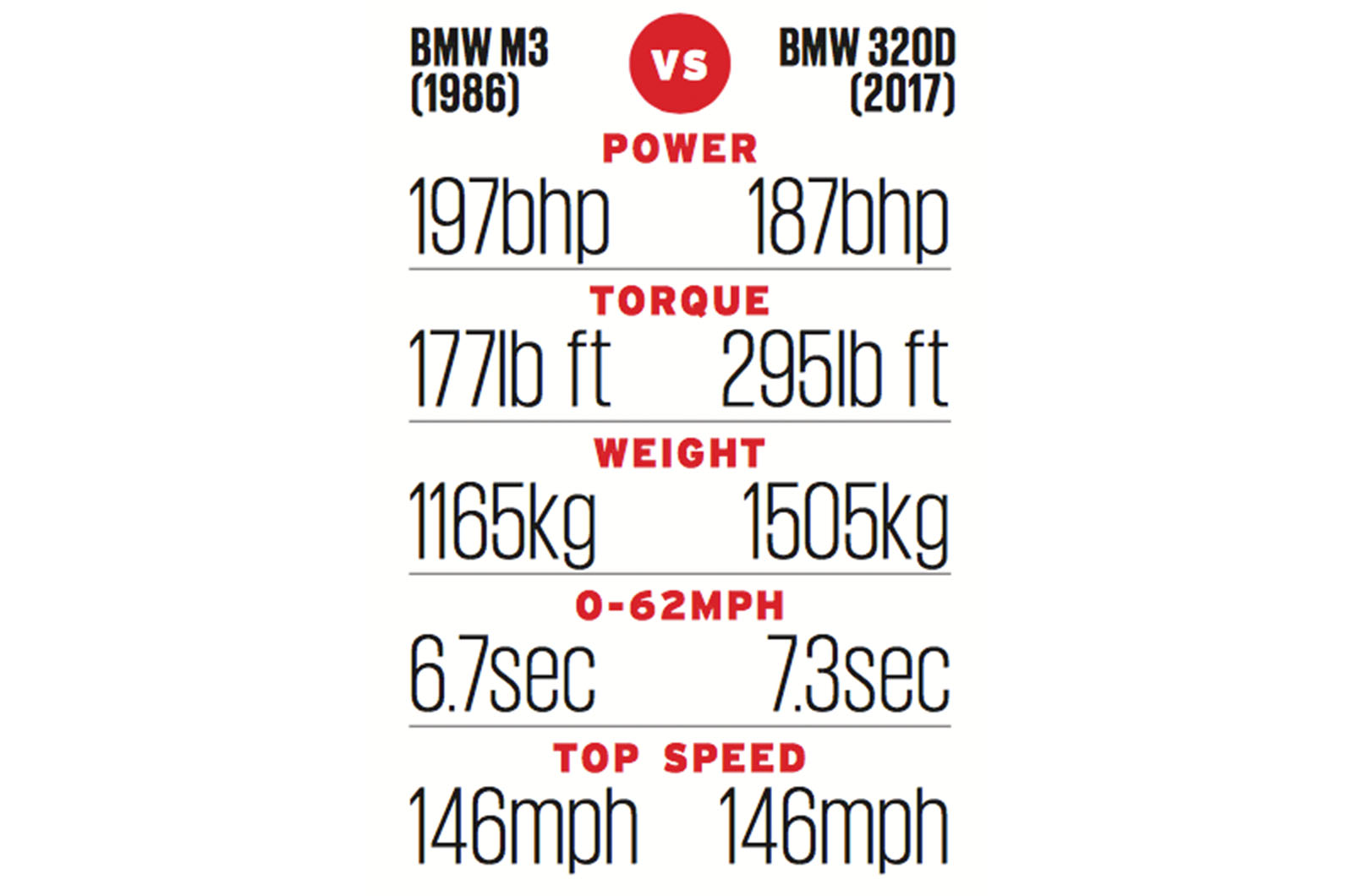

BMW M3 (1986) vs BMW 3 Series 320d

It may have just looked like a hotted-up version of an E30 BMW 3 Series, but the original BMW M3 was nothing less than a track car in road-legal form. It existed only to homologate its racing version into Group A competition and came not only with a bespoke racing motor but its own body, completely different suspension, brakes and a Getrag gearbox with its trademark dog-leg five-speed layout.

The four-cylinder engine displaced 2.3 litres and generated 197bhp, giving a specific output better than that of any production Ferrari on sale at the time of its launch in 1986.

Spool forward 30 years and even a diesel-powered two-litre 3 Series has a better specific output and, despite enormous weight gain, is capable of staying within sight of the old M3 off the line: for that, thank an even more gigantic increase in torque. Flat out, there is not a single mile per hour between them. So, in bald terms, BMW’s everyday meat and two veg, top-selling motorway muncher is now nearly as quick as one of its finest, race-bred, bespoke and coveted performance cars of three decades ago.

Actually, although the figures do not reflect it, a modern 3 Series 320d actually feels quicker than an old M3 and, yes, part of me is sad to say it. It’s that torque again, not just the amount but the fact it’s all there at 1750rpm, at which point the M3 has just opened its eyes, swung its legs out of bed and is looking for its slippers. It really wants to be at 4500rpm before it’s up and running, at which engine speed the 320d is already wondering why you’ve not changed up. In the M3, it’s not a question that needs an answer: in deference to the car’s age, I’m not about to go prodding about north of 7000rpm, but I remember well that these brilliant little BMW Motorsport engines go on sounding happier and happier until, just as you think it’s really getting into its stride, it hits the rev limiter.

But even over a lap of a quick track, I wouldn't back the old M3 over the new 320d. Maybe if you put the M3 on modern rubber, it’s geometrically optimised suspension would combine with its relative lack of heft to allow it to keep up with the younger car, but I doubt it: the 320d not only has the mid-range punch but also the brakes and, on a high-speed track, aerodynamic efficiency that I expect would let it retain the upper hand.

Except for this: drive the 320d around a quick track and you will emerge impressed at how fast, secure and able a car is in an environment for which it was not remotely designed. But doing the same in the M3 is an experience of an entirely different calibre, which is where technically the quicker of the two fast becomes an irrelevance. It’s like bumping into your best friend for the first time since emigrating 30 years ago, going to the pub and realising you still both want the same things, laugh at the same jokes and remain itching for adventure. You pick up where you last left off. There’s no need to remember to pull back instead of push forward to get first gear: your hand just instinctively does it. And then, when you’re out there, slithering around together, feeling that perfectly weighed and geared steering wheel writhing gently in your hands, you remember exactly why this M3 will always be a performance car icon, and the 320d always an effective, efficient device for doing a rather boring job.

I mean the 320d no disrespect by saying that, for it is the most impressive car of its kind there is, but it is a tool and no more. The M3, on the other hand, is a toy and, when you want it to be, a weapon, too.

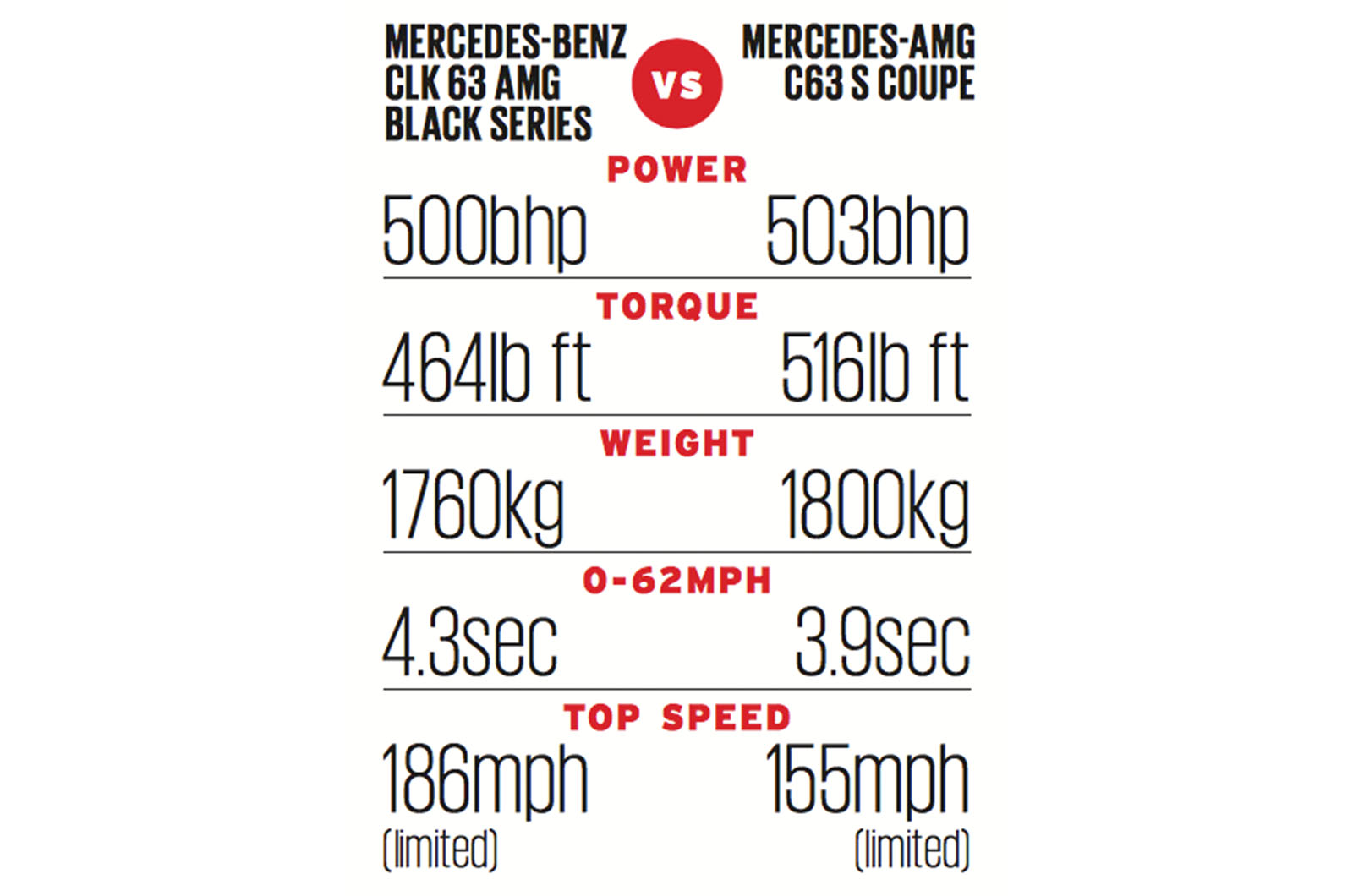

Mercedes-Benz CLK 63 AMG Black Series (2008) vs Mercedes-AMG C63 S Coupé

So we know what a difference 30 years’ development makes, and perhaps we should not be too surprised that what is accepted as normal today was regarded as exceptional a generation ago. So let’s narrow it down a bit. How far have performance cars come in, not 30 or 20 years, but just 10?

Ten years ago, the CLK Black Series was the first car to signal unambiguously that Mercedes was serious about building its own performance cars in a way it had not been since the days of the Gullwing back in the 1950s. It wasn’t the first Black Series car (but the less said about the SLK 55 Black the better), nor was it ever the quickest Mercedes, because it came at the same time as the very flawed, McLaren- engineered-and-built SLR. It was, however, the first credible car to wear the Black badge and set Mercedes on a course that led directly to the Mercedes-AMG Project One hypercar. And, by any standards, it was an extreme machine.

The fact that engine power had been raised from 478bhp to 507bhp wasn’t really what mattered, it was what had been done to keep it all in check. Most obviously, Mercedes widened the CLK's track by 66mm at the rear and an enormous 75mm up front, then had to build those blistered wheelarches to accommodate. An even bigger clue to the track- oriented nature of the car was that its suspension was not only bespoke but fully adjustable.

It had superlight forged wheels, an aero pack including a carbonfibre rear wing that cancelled lift, a reprogrammed gearbox and, inside, lacked rear seats. AMG itself said the car was inspired by the Porsche 911 GT3 RS. It really was that kind of machine.

And when you drive it today, it does not disappoint at all. It feels fast rather than hells-bells rapid, but that enormous 6.2-litre normally aspirated V8 feels like it should be powering a racing car. Despite its size, it really needs revs to work – but, when it does, your ears are greeted by the finest soundtrack any Mercedes has yet made.

Better still, the chassis is superb. The limited-slip differential at the back was fitted with its own oil cooler for the Black Series and, given how hard it works, I’m not surprised. This is a car where, once you’ve used a bit of power to wrench the back loose, allows an angle of yaw directly proportional to position of the throttle pedal. It is terrific, one of those few cars that does not disappoint at all after a decade away.

But the brand new, off-the-peg C63 Coupé is no less captivating. Its twin-turbo V8 sounds damn near as good and needs no tempting with your right foot at all. Lag is effectively absent. It has more torque at 1750rpm than the CLK can muster in total. Whether you fire it down a straight or through a corner, it's the quicker car.

As for the CLK's handling, it’s not quite so keen to slide, which is probably a good thing most of the time, but it’s still pretty willing and, when it does, it’s no less deliciously controllable. Even the steering, which I thought would have suffered most in the last decade, is as accurate, linear and full of feel.

Yet the modern C63 does all the other stuff too: it rides well, it’s quiet on a constant throttle and it’s brimming with gadgets, none more useful than those big comfortable things in the back called seats.

So it’s not as if Mercedes could not reach this level of ability 10 years ago, merely that the car had to be massively compromised to do it – a wonderful toy, but a toy nonetheless. By contrast, if you’re not using the C63 as a daily driver, you’re missing out on what it does best.

One more thing: in 2007, the CLK Black cost just a few quid shy of £100,000 – 30 grand more than the C63 Coupé costs today. And as a real measure of progress made in such a small period of time even as this, I know none better.

Related stories:

Comments

Post a Comment